Future food

Human behaviour is negatively impacting on our food supply. The more insidious effects of climate change and other human-induced environmental woes are one cause. Another more immediate cause is that policy decisions on resource use and exploitation are being driven from a misguided agenda of short-term gain. Judging from the increased exposure in traditional media sources, a potential crisis is brewing.

agenda of short-term gain. Judging from the increased exposure in traditional media sources, a potential crisis is brewing.

The reason for the exposure? Soaring food prices worldwide. Food prices worldwide have increased by 40% in the last year. In the US, the current amounts of food inflation have been unseen since the 1970s. While some of this increase in the result of increased drought over many areas (a sign of climate change?), for instance in Australia, much of it is due to humans and the policy decisions made for us. The increasing diversion of grains, especially corn, to the production of ethanol and other biofuels is a major culprit in the price rises.

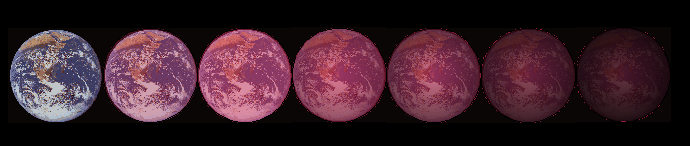

This is just the immediate threat. Warming temperatures, increasing droughts and the like – the expected effects of climate change-- will likely make agriculture more difficult in the near future. It is not just now we should be worried about, but the future as well.

Indeed, the effects of climate change are already being felt. The regions of the earth that experience tropical weather are expanding poleward, likely to bring a change in traditional growing conditions in a given area. Such shifts are being noted in around the world:

China is seeing its rice producing regions shift northward, as severe drought plagues the south.

In Japan, rice crop yields in the premiere growing areas have been in decline as summer heats up to unprecedented levels over the past few years.

In Africa, meat, poultry and vegetables are all feeling the impacts of climate change. For example, plant and livestock diseases have been recently observed areas where they previously have not been seen.

Rising CO2 levels may also effect aquatic food sources like fish, wither directly through ocean acidification or indirectly by alterations in oceanic bacteria, the basis of life on our planet. Despite the harsh realities already being felt, some recent research suggests that we may be underestimating the likely effects of climate change on agriculture, as previous research was likely oversimplified and failed to account for important second-order effects.

So what to do? A necessary step is to expand research in this area. Investing in new, heartier crop varieties like heat-tolerant beans or higher-yielding wheat is essential. Also crucial to understand are farming methods to maintain production levels with less fossil-fuel-based fertilizer. In general, the whole idea of mass-produced industrial agriculture will be nonviable. Having enough to eat without cheap oil is going to be tricky. Ask the Cubans (with sarcastic commentary from Bruce Sterling). Food is going to have to be produced more locally. Nations (like Australia) will have to ensure the capacity to feed themselves. Whether you are a nation, a tribe or an individual, when push comes to shove and resources are scarce, human nature says you will be unable to rely the goodwill of neighbours. (But growing enough of you own food is hard work...). New areas for growing food, indoor and urban growth for example, will also have to be exploited. That said, expanding cultivated land by clearing forests is likely to lead to diminishing returns. Agriculture and climate change is a two-way interaction.

A shift in our policies to something more sensible is needed. Human beings, not economic systems, should be our primary concern. For example, recent bumper harvests in Malawi suggest policies set by organizations like the World Bank to instill some rigid ideological economic purity reduce food amounts and cost human lives. The increasing push for biofuels is also short-sighted. Do you really need to deprive people of food so that you can go to the mall and buy some useless junk? Sustainable policies -- those that will provide a benefit now, but also conserve to provide a boon next year, next decade and next century – are also desperately needed. Instead, our current focus is on the needs of the economic system. The recent decision to raise the North Sea cod quota is just such an example. A slight upturn in surviving baby cod numbers results in an 11% increase in the catch. Great! Let's risk the future for a profit today! The failure of the recent Bali climate to set a meaningful target for climate change mitigation is another example. This mostly occurred because of the constant obstruction of the US, worried solely about themselves and their profits.

Not having enough food is a sure-fire step to instigating societal collapse. The time for profit uber alles is over. The time is now to focus on preserving the environment and our food supply for now and future generations.

***Image: iStockphoto/Susan Stewart